Recent Additions

Lord Keep me in Teepee Top Shape

This Precious Moments figurine depicts a Native American Indian boy eating spinach. It was a 1991 sp..

Granddaughter Ornament 1994

This Hallmark ornament depicts a beaver holding an ice cream cone and wearing a salmon-colored dress..

You're My Winters Joy Ornament

This Pretty as a Picture ornament depicts a young boy skiing and looking a little unstable on his sk..

McClellands: John

This figurine from Reco is part of The McClellands collection, designed by John McClelland. ..

I'm On My Way To You Ornament

This Pretty as a Picture hanging ornament depicts a boy skiing. Introduced in 1998, this Christma..

Love Blooms

This Dreamsicles figurine features a cherub seated with a bucket of purple flowers. This figurine..

I Picked You to Love Photo Frame

This flower-shaped ceramic photo frame was issued by Precious Moments in 2004. It features a relief ..

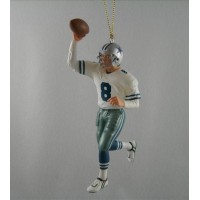

Troy Aikman Ornament 1996

This Hallmark ornament is the second in the Football Legends series, produced under license from Cla..